To Winter Well

A happy February to you. It has been cold in an enduring sort of way in Virginia, and my housemates and I are getting good use out of our slippers, socks, and space heaters in our big, drafty house.

Winter is marked by extra care, those small things you don’t think to do when you’re young, but the things that really improve the quality of wintry life: the humidifier running, the moisturizing after every shower, the big pot of soup simmering for hours, the meticulous de-icing of the stairs. Extra layers.

I’m not really keen on doing any of these extra steps, though. In the winter, I’m impatient, most often daydreaming of strolling out the door without needing to put a coat on. I’m dry and itchy, and it really feels like I wear the same outfit every day.

I like to think about how people can live well where they are, and how to discern what is divine and life-giving there, but winter often feels like a roadblock. Perhaps it feels less carefree than I’d like it to. It’s not easy for me to see it as a life-giving place; it’s easier to daydream about the day when summer comes, when the tree across the street will be full-leaved. Things will be easier, then.

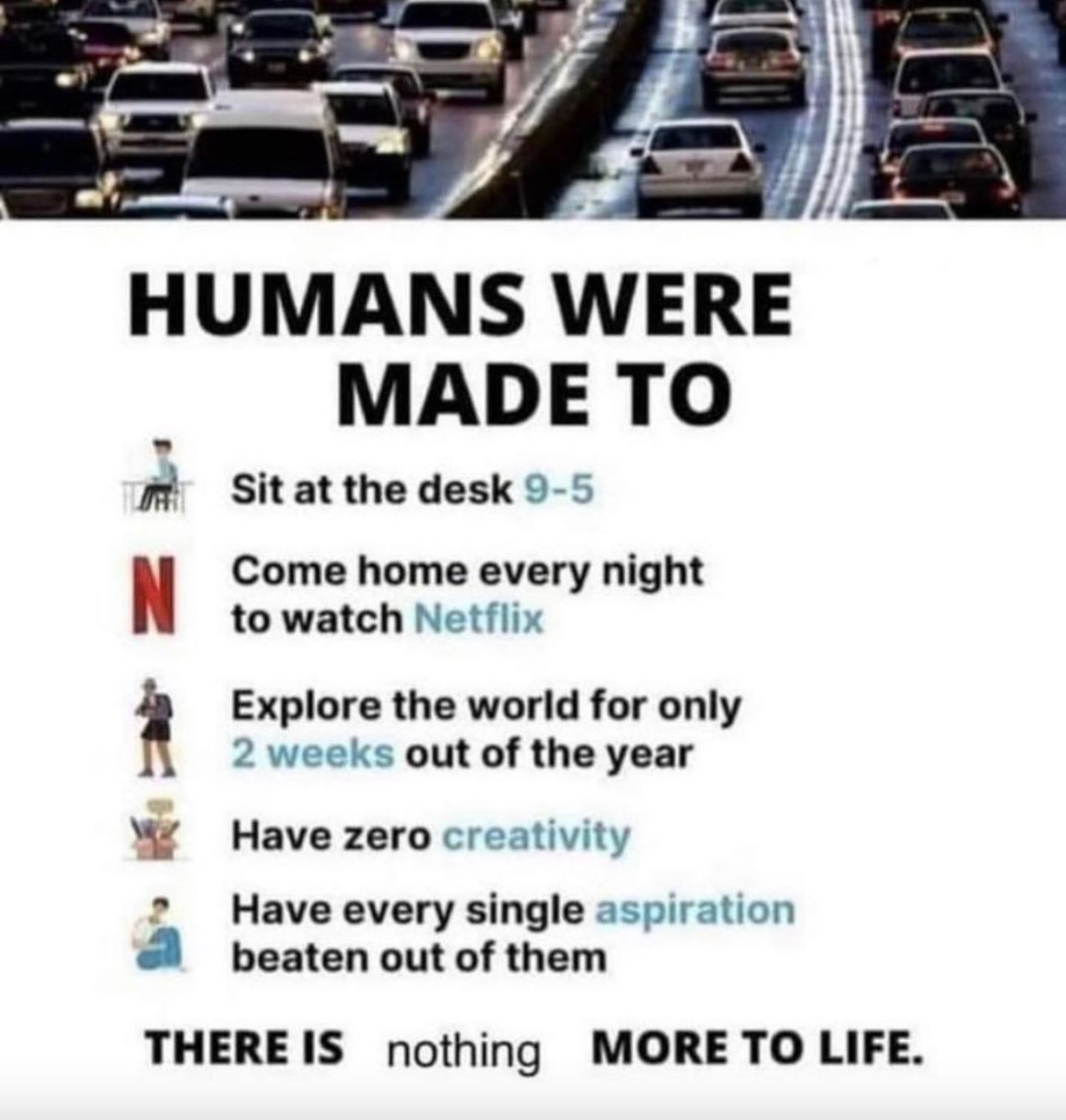

But maybe winter is not the enemy here – maybe that end goal of becoming carefree is. I think a hatred of winter is just part of a larger cycle of waiting for the better thing to arrive. Winter is just the workweek of the seasonal year, the Monday after the glorious weekend that autumn was, the monotony we’re waiting out until the Friday that the first warm spring days seem to signal. The problem with that line of thinking, though, is that we spend a lot of life in winter, and in our workweeks.

Maybe we weren’t just made for the weekend, for the summer, for the vacation. Maybe there’s more to life than just looking forward to an easier time – maybe there are good gifts to receive and good lessons to learn for us now, today, in the seasons we are in.

During a visit to Southborough L’Abri in Massachusetts (during a very bleak winter in early 2018), I heard this quote by Parker Palmer that I have been mulling over for four years now:

In the Upper Midwest, newcomers often receive a classic piece of wintertime advice: “The winters will drive you crazy until you learn to get out into them.” Here, people spend good money on warm clothing so they can get outdoors and avoid the “cabin fever” that comes from huddling fearfully by the fire during the long frozen months. If you live here long, you learn that a daily walk into the winter world will fortify the spirit by taking you boldly to the very heart of the season you fear.

Our inward winters take many forms—failure, betrayal, depression, death. But every one of them, in my experience, yields to the same advice: “The winters will drive you crazy until you learn to get out into them.” Until we enter boldly into the fears we most want to avoid, those fears will dominate our lives. But when we walk directly into them—protected from frostbite by the warm garb of friendship or inner discipline or spiritual guidance—we can learn what they have to teach us. Then, we discover once again that the cycle of the seasons is trustworthy and life-giving, even in the most dismaying season of all.1

Maybe, like Palmer says, it’s worth taking a look at our lives and the things that we avoid venturing into, where we opt instead for nostalgias or daydreams, and consider how we might face our winters, physical and otherwise.

I am taking the month of February (our last certain winter month here in Virginia) to explore wintering well. I’ll explore nurture, preparation, and methods for cultivating joy and tending to an impatient heart – an experiment for myself, but one that may also encourage you. (And I’ll include a review of Katherine May’s Wintering, because of course.)

Parker J. Palmer, Let Your Life Speak: Listening for the Voice of Vocation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000.